Vivisection: a history in copper

Before we were Animal Concern, we were the Scottish Anti-Vivisection Society (SAVS). Dating all the way back to 1876, we campaigned for an end to the animal experimentation over several decades. In the days before word processors, we used printing presses to print and disseminate our campaign material to the general public, using photographically engraved copper plates which were pressed onto leaflets and educational pamphlets.

Many of these plates have survived to this day.

They tell a grim story of exactly what vivisection looked like back then, and serve as a haunting reminder of the cruelty inflicted on animals even now.

Introduction

Throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, scientific experiments were conducted on animals throughout the world in the name of research. Scientific credence was widely given to the theory that animals could serve as accurate models for human physiology. In the UK, the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876 marked the first legislative attempt to regulate the practice. The Act required researchers to obtain licenses and imposed some restrictions on the types of experiments permissible. Nonetheless, it was criticised for its limited scope and lack of effective enforcement.

The Two-Headed Dog

In the early 20th century, the infamous two-headed dog experiment was conducted by Vladimir Demikhov in Soviet Russia and it became a symbol of the unnatural barbarism of vivisection. A so-called “pioneer” of organ transplantation medicine, Demikhov surgically connected the circulatory systems of two dogs, leading to the creation of a two-headed living creature. It raised concerns worldwide about the boundaries of scientific ethics and the need for tighter regulations on live animal experimentation.

A photographic copper printing plate of Demikhov’s two-headed dog. It survived like this for 6 days.

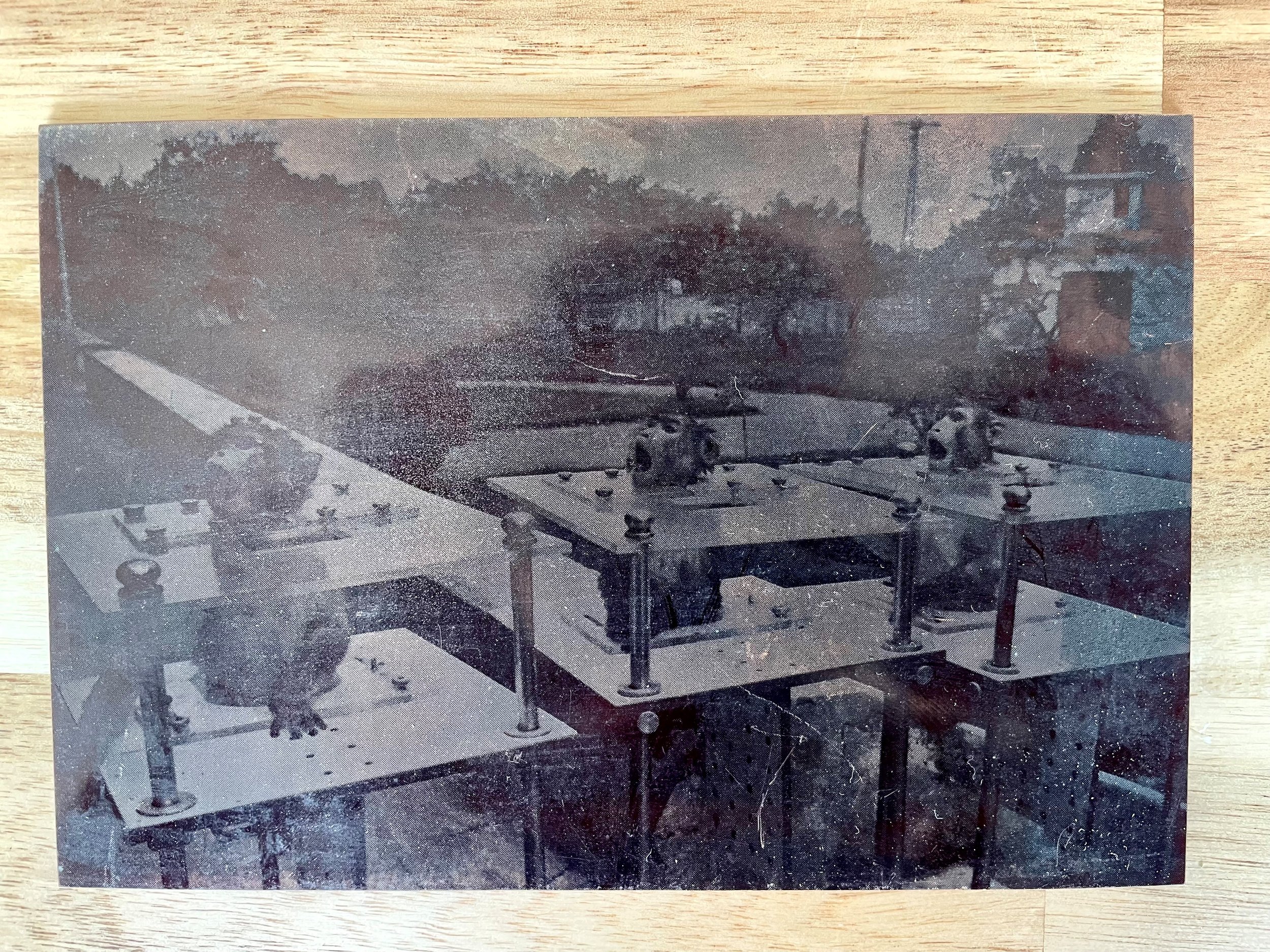

Tobacco and animal cruelty

Tobacco testing on animals was another contentious issue that gained public attention during the mid-20th century.

Experimenters would attach tubes to holes in the necks of dogs and monkeys, or strap masks to their faces, as shown, to force smoke into their lungs.

This led to severe health issues and fatalities.

Another test was to apply cigarette tar directly onto the bare skin of mice and rats to induce the growth of skin tumours.

This practice sparked significant outrage among animal rights advocates and fueled the growing anti-vivisection movement.

Today, tobacco product development and testing is banned in the UK as well as Estonia, Germany, Belgium and Slovenia. But that’s it...

The Thalidomide Scandal

Perhaps one of the most notorious episodes in the history of vivisection was the Thalidomide scandal, which unfolded during the 1950s and 1960s. Thalidomide, a drug initially marketed as a sedative and treatment for morning sickness in pregnant women, was widely tested on animals before being released to the public. Tragically, the drug caused severe birth defects, resulting in tens of thousands of babies being born with limb deformities and other life-threatening conditions. Around 2,000 babies died. The incident exposed the inadequacy of animal testing in predicting human reactions to drugs and underscored the necessity for more stringent safety measures.

Though difficult to make out from this photo, this printing tile shows the effects of the animal-tested thalidomide drug.

Born with few or no limbs, artificial ones were created and strapped to the children.

In the wake of these controversial events, public outcry and mounting pressure from animal welfare groups, including SAVS, led to the reform of vivisection regulations.

Vivisection legislation

The Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876 was eventually replaced by the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. This legislation aimed to strike a balance between the need for scientific research and the ethical treatment of animals. The Act introduced a three-tier system of classification for experiments, with increasing levels of scrutiny and regulation for experiments that involve more severe suffering for animals. The Act also established a system of licensing and supervision, emphasising the “3Rs” principle - Replacement (of animal testing methods with other humane means wherever possible); Reduction (in the number of animals subjected to experimentation); and Refinement (in the procedures themselves so as to incur as little suffering to the animal as possible).

In 1998, a ban on animal-tested cosmetic products was implemented in the UK. Eight years later, the Animal Welfare Act 2006 enshrined into law the obligation to minimise the suffering of animals. In 2010, the European Union’s Directive 2010/63 was passed to regulated animal welfare standards, which became UK law in January 2013. And in 2015, a ban was instated in the UK for animal testing on household products.

Animal testing today

Despite these steps towards progress, the Home Office reported that in 2021, there were more than 3 million tests conducted on animals in the UK. It is illegal to test on animals if there is another way conducting the research. But new medicines must be tested, by law, on animals before being trialled on humans.

Alternatives to animal testing have to be an absolute government funding priority. We know that we have the technologies now to be able to conduct research using in vitro testing, computer modelling and human cell-based studies. In a self-professed nation of animal-lovers, we cannot allow the continuation of this cruel and morally abhorrent practice, which can never be 100% accurate due to the innate biological differences between humans and other species.

We are well overdue in shifting towards human-relevant and ethical medicine and science, and never again subject our animals to anything to which we wouldn’t subject ourselves.

There have been many UK Government petitions on the subject of ending or reducing animal testing in this country. The only one still live, with a deadline of 8th September 2023, is to “End the use of animals in toxicity tests & prioritise non-animal methods (NAMS)”.

Evidence shows NAMs to be more predictive of human biology, more economically advantageous via new prospects in scientific innovation, and prevent the suffering of millions of animals.

Its aim are to:

Radically divert funding and evolve policy to implement the use of NAMs in all regulatory toxicity tests.

Actively encourage use of NAMs, noting that this data is of superior human relevance compared to animal tests data.

Establish clear pathways to develop & validate NAMs and end the use of animals.